Sensing the government was moving towards interoperability and a government backed interface was readily available, many payment service providers promoted UPI aggressively

Unified Payment Interface, UPI for short, has been a game changer in the Indian payment system. The rise of UPI, developed by National Payment Corporation of India (NPCI), has not just democratized digital payments in India, but also picked up on value term. There is hardly any parallel to such a spectacular growth anywhere else in the world, not to talk of the developing world with so little digital penetration.

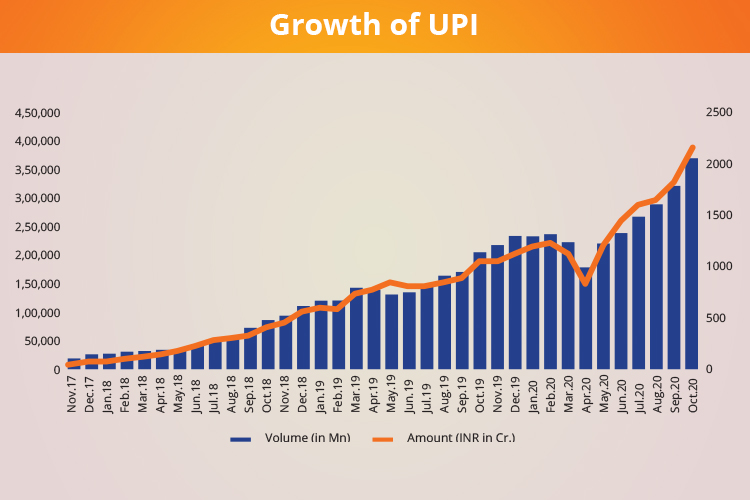

In October 2020, UPI transaction volumes topped two billion. That is a 20-fold rise in monthly transactions over the last three years. In terms of value, last month saw a total of INR 3,86,107 crores being transacted, which is a 40-fold increase in monthly values being transacted in the same period. They translate to a whopping 170% average annual growth (CAGR) in terms of number of transactions and 242% CAGR in terms of value being transacted on UPI every month. That is impressive by any standard.

The fact that values have grown at a significantly higher rate than number of transactions shows that the popularity of the system has not just resulted in its widening UPI’s base but also its depth of usage.

A comparison with a similar system will put the growth in context. In FY 2016-17, IMPS transactions totalled 507 millions with a total value of INR 4,11,624 crores. UPI, on the other hand, totalled 17.86 million transactions with a total value of less than INR 7,000 crores. The corresponding figures for the last year (2019-20) for IMPS were 2,579 millions (more than five times) and the value transacted was INR 23,37,541 crores (close to four times). UPI, by the way, had grown to 12,519 millions (about 70 times) while value transacted on UPI rose to INR 21,31,330 crores (more than 300 times). In the first six months of this year (FY 20-21), UPI had already done 8,487 million transactions with a value of INR 15,49,240 crores while IMPS had done about one-seventh in terms of transactions and about 20% less in terms of transacted value, UPI having overtaken IMPS in February this year, in terms of value—and thus establishing itself as the prime mode of retail transaction.

Wallets, which actually kickstarted digital payments in a major way, accounted for 397 million transactions as compared to UPI’s 1,619 million transactions. Value of transactions would not be a fair basis for comparison as wallets have restrictions of INR 10,000 per month without KYC and INR 1,00,000 per month with KYC. UPI, on the other hand, does not require any KYC, as that responsibility is with banks, anyway. So, higher valued transactions can be done. In fact, UPI transaction limit of INR 1 lakh per day is not an issue for most of the ordinary users.

UPI, which has often been described as the brainchild of former RBI governor Raghuram Rajan, and his ‘parting gift’ to India because it was launched a few months before his tenure ended, has since then, been aggressively promoted by the government.

Three reasons have contributed to UPI emerging as the most popular retail payment mechanism – a number of inherent features, almost no cost to the user and the merchants, and very aggressive promotion by the government.

First and foremost: the user does not have to block his/her money, as in case of wallets which popularized digital payments. Money is directly transferred from the bank account. UPI is also interoperable. A merchant can accept money from any of the payment apps used by the payer. However, a major constraint for many users is that the wallet transaction value is capped at INR 10,000 per user if KYC is not done. KYC is a major inconvenience for the user and is costly and time consuming for the wallet service provider. In UPI, there is no need for any KYC, as the bank has already done the KYC. So, that is a major hurdle removed for both the parties—users and payment apps.

When it comes to P2P money transfers, unlike direct IMPS, a UPI-based transfer can be done immediately without waiting for the payee to be activated by the system. While for the friends and family, it is still a good option, few would like to add a Kirana store or a petrol station to their payees in their bank account. Finally, you need not know/share the bank account number, and IFSC code of the bank branch which does not just make it more convenient to use, but also makes it safer in the eyes of the user, as not many are comfortable in sharing one’s bank account number.

In addition to that, UPI has been aggressively promoted and incentivized by the government. From Prime Minister to IT minister and all senior government officials have promoted UPI directly on social media. In addition, MDR (merchant discount rate) for UPI transaction was mandated to be zero by the government. What it means is that UPI transactions now do not cost anything to the payee (including the merchant) or the payer. That is another huge reason for the popularity of UPI.

Finally, the government has also promoted UPI consistently. From Prime Minister to IT minister, all have talked about UPI publicly.

The UPI ‘Market’

Sensing the government was moving towards interoperability and a government backed interface was readily available, many payment service providers promoted UPI aggressively. Especially for the challengers to Paytm, which benefitted immensely from it being ‘at the right place, at the right time’ during demonetization and was clearing zooming ahead, it was a good rallying point.

Google Pay built an early lead in the UPI-based payment market, while PhonePe was a distinct and somewhat distant second. Paytm too moved aggressively and has now picked up market share but Amazon Pay has also emerged as a major challenger. Latest market share figures are not available, but according to a Bernstein estimate, as reported by Business Insider, in May 2020, Google Pay held 38.4% share, while PhonePe had 19.8% share. Amazon Pay and Paytm had 16% and 15.5% shares respectively. Another report by TechCrunch, based on NPCI data suggested that Google Pay had 540 million UPI transactions, PhonePe had 460 million while Paytm saw 120 million in the same period. Since then, Amazon Pay has clearly increased its share.

Earlier this month (November 2020), as UPI volumes topped 2 billion transactions per month, NPCI put a cap of 30% share of total volume of transactions processed for any single third party application provider. This will come to effect from 1st January 2021. The existing providers exceeding the specified cap will have a period of two years from January 2021, to comply with the same in a phased manner. The cap of 30% will be calculated basis the total volume of transactions processed in UPI during the preceding three months (on a rolling basis).

NPCI said it “will help to address the risks and protect the UPI ecosystem as it further scales up.” Expectedly, the two top players, Google Pay and PhonePe—incidentally both owned by foreign companies, Google and Walmart respectively, have criticized the decision, saying it will negatively impact the users.

While we do not get into that debate in the story, one thing is for sure. The UPI volumes are showing no signs of slowing down.

As discussed above, three reasons have contributed to UPI emerging as the most popular retail payment mechanism – a number of inherent features, no cost to the user and the merchants, and very aggressive promotion by the government.

What needs to be examined is how important are the three reasons in comparative terms. For something to sustain in the market, it has to compete on natural market parameters, not artificial parameters like the last two, cost and government push.

Is it sustainable?

It may be too dramatic to ask if UPI is sustainable, considering the threshold volume that it has already reached. But for the same reason, it is important to examine whether the underlying infrastructure is ready to support these rising volumes.

Early signs about the cracks were already evident from 2018. Users have been complaining about false success notifications; i.e. while the app said the transaction was successful, the money was not credited to the receiver’s account. Despite several follow-ups with their banks and NPCI, the issue took a long time, paper trail and exchange of several messages to resolve. In a report in March 2018, business daily, Business Standard wrote about the problem, citing several aggrieved users of UPI.

But with very tangible convenience and cost advantages, these ‘exceptions’ did not adversely impact the popularity of UPI as a payment mechanism.

After all, such exceptions were few and far between. These errors happen when the transaction is declined due to technical reasons, such as unavailability of systems and network issues on bank or UPI side and are hence called technical declines (TD) to distinguish them from declines due to user side issues, such as wrong PIN, wrong account number, violations per transaction or per day limits, etc, which are called business declines (BD). While the business declines are not due to the UPI system, technical declines are clearly due to issues on the system side.

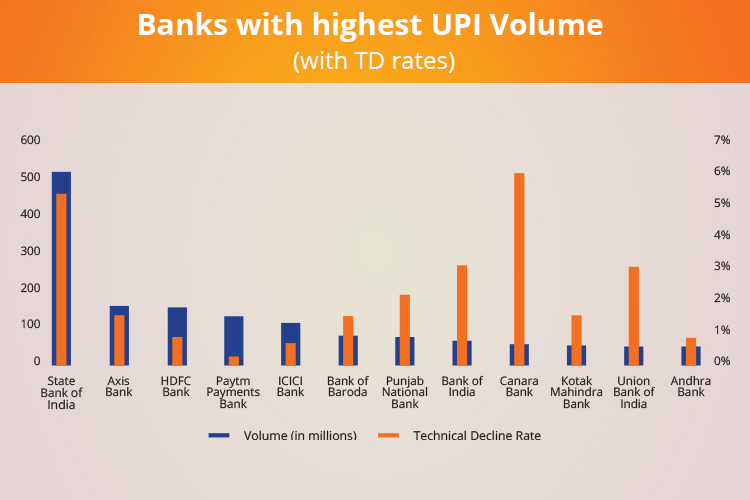

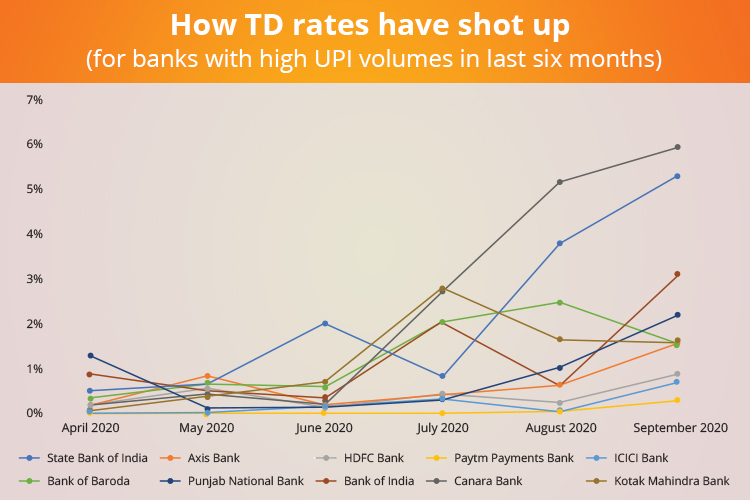

Till as late as in March this year, these technical declines ranged between 0.1% of transactions to 1.91% of transactions for different banks. From the eight banks that saw high transaction volumes (more than 30 million per month), seven had less than 1% technical decline rates. That was not something to be get too concerned about, even though the largest of them, State Bank of India, had seen 1.84% technical declines.

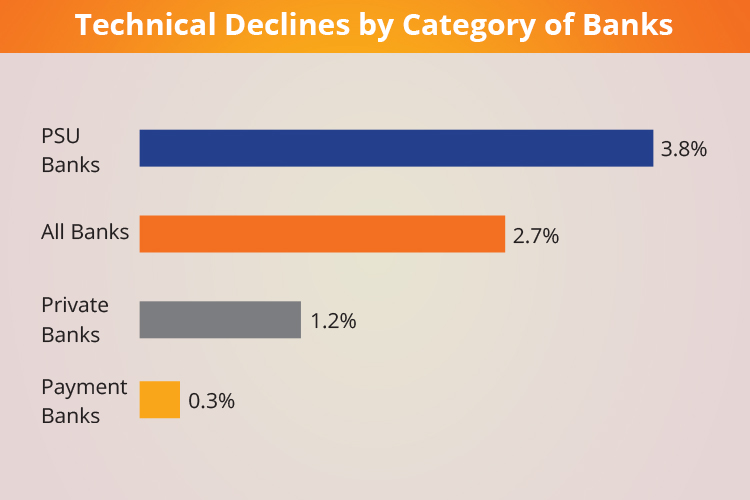

Things have deteriorated sharply. In September, the technical decline rate had reached 2.7% of total transactions. For banks with larger transaction volumes, it was even higher at 2.9%. As many as eight of the top 30 banks whose data is available had more than 3% technical decline rate, with some touching almost 6% (Canara Bank, 5.93%). State Bank of India, which accounts for 27% of all transactions executed by these 30 banks, had 5.31% technical declines.

But what is revealing is the sharp contrast that exists between public sector and private banks. While the 11 private sector banks saw a technical decline rate of only 1%, the public sector banks’ TD rate was almost four times higher at 3.8%. Within private sector banks, both the payment banks – Paytm Payments Bank and Airtel Payments Bank - saw technical decline rates of less than 0.4%.

The reason for this contrast is not too difficult to guess. Many of the public sector banks have aging digital infrastructure, which are probably not equipped to handle these high volumes. UPI transactions require almost real-time communication involving five servers—payer payment service provider (PSP), remitter bank, UPI system, payee PSP and the receiver bank. Any latency or break in communication can result in transaction failure. In times of high volumes of transactions, the server may choke. Since the UPI request hits a bank’s core banking system, unlike the wallets, it puts pressure on the bank infrastructure.

So, even though Paytm Payments Bank and ICICI Bank have high volumes, their technical decline rates are quite low. Most older banks need to upgrade/modernize their infrastructure to ensure that technical declines are minimized. Private sector banks and the new payment banks have state-of-the-art digital infrastructure that handle the transactions better.

But thanks to the zero MDR rule mandated by the government last year, banks are not supposed to charge any fees, which means they do not earn anything from the UPI transactions. So, they have little incentive to upgrade the infrastructure.

Banks and NPCI have been voicing these concerns and have been demanding zero MDR rule to be changed. But even if the government listens to that, it is highly unlikely that things will immediately change for better.

Another potential threat in the future is the vulnerability of the NPCI system. NPCI has capped the share of transactions of any single payment company in order to decrease dependence on any single third-party application, to avoid a system failure. The same question could be asked about the NPCI system too. While the UPI system uptime has been maintained above 99.8% every month since January, that could be vulnerable too. And even 99.83% (April) or 99.85% (September) are low by a real-time transaction system standard.

In short, while UPI has had a successful run so far, past performance cannot be guaranteed.

For the banks, which have to keep their customers, there is no option but to modernize their digital infrastructure to handle high volumes of real-time transactions, as volumes will only go up. Of course, the government decision on zero MDR is hurting them. But even if the government reverses the decision, things will not dramatically improve overnight. It needs thorough technology planning that could take several months to execute.

When Raghuram Rajan had envisaged such open payment systems, it was part of a bigger vision to push banks to adopt digital technologies. However, while UPI has been milked, many of the other components of that vision are missing. It is not surprising that we are seeing gaps.

Beyond UPI too, banks need to assess their readiness for an increasingly 24-7 transactions world with high volumes of transaction. That is the next challenge for Indian banks, especially the public sector and old private sector banks. There is no other alternative.

In

In

Add new comment